California, Chinese Pride and the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad Part I

【Summary】California, Chinese Pride and the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad

By Anthony C. LoBaido

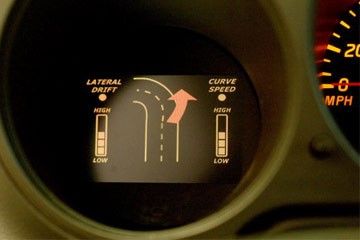

The involvement of erudite ethnic Chinese in some of California's greatest postmodern technological innovations routinely makes national and even global headlines. Consider YT Jia of LeEco and William Li of NextEV as just a few of the many examples one might cite.

There can be no doubt that Chinese involvement with the autonomous automobiles of the 21st Century will be forever linked with the railroad cars of the 19th Century. Yet how many children living in China today know about the long proud heritage of their people who once labored in the state of California? This epic tale has been called "The Work of Giants" as one notable person put it. It involved the building of the transcontinental railroad. And it is a feat that rivals, in its own way, the building of the Great Pyramids in Egypt, the Panama Canal and the Empire State Building. It should be noted that Leland Stanford, the founder of The Stanford University, was one of the main proponents of building the transcontinental railroad. It was a race in which iron men mastered iron rails to link the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Before the building of the transcontinental railroad, it could take travelers six months to cross treacherous rivers, mountains and deserts to get from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. (At a cost of $ 1,000 which was a small fortune back then.) As noted, crossing the American continent before the advent of the transcontinental railroad was considered "a slow waltz to the moon." The journey could be life-threatening and this is not hyperbolic. There were avalanches to content with. And attacks from American Indian tribes were always a concern.

Alternately, it was possible to take a six week voyage around Cape Horn. Magellan became terribly vexed when he first encountered this tricky maritime chokepoint on November 1, 1520 — better known as "All's Souls Day." As such, they were originally called "Estrecho de Todos los Santos" or "Strait of All Saints." The Straits of Magellan between extreme southern Argentina and Antarctica comprise some of the most volatile waters on Earth. Navigating them, even today, with postmodern radar, sonar and similar technologies, is no easy task.

There was a third way to cross the United States that should also be mentioned – taking a ship to Panama and then crossing the Isthmus by land on horseback for a month – while facing Yellow Fever and Malaria. A new railroad linking the East Coast to the West Coast would solve all of these aforementioned problems.

Between the eras of Jacksonian America and Abraham Lincoln, "the West" was viewed with much of the same fascination one might reserve today for outer space. Remember that back in the 1830's and 1840's transportation was almost exactly the same as it was in ancient Rome. Animals pulled along carts at four miles-per-hour. The steam engine, which was invented in the United Kingdom in 1825, changed of all that. Now you could travel between 20 – 40 miles per hour and cover the same ground in one day that otherwise might have taken a week. By 1850, there were 10,000 miles of railroad track set down east of the Mississippi River. However, trains were still in their infancy and travel has been described as "dangerous and dirty," subject to fires, steam and various breakdowns. Like the automobile industry of 2016, the railroads of that epoch were ripe for a paradigm shift.

Conquering the West all the way to the Pacific Ocean meant successfully building the transcontinental railroad. Scholars say that for President Lincoln, the building of the railroad was "not a commercial act or an act of technology," but merely to make the nation strong and whole. To heal the divide of north and south, east and west would have to be united.

In the year 1862, Kansas City was the most-western train depot. To go from Kansas City to Sacramento meant 1,600 miles of track had to be put down. There were not one but two mountain ranges in the way. The Rockies and the Sierra featured peaks of 14,000 feet. There was the Great Salt Lake Desert to content with.

"If you build it, they will come"

Chinese immigrants first came to California to begin working at "Gold Mountain," which is what they called the 1849er Gold Rush. The 1849ers included 325 Chinese immigrants. Three years later, by 1852, around 20,000 Chinese had arrived in the state. Chinese immigrants were some of the initial city planners for San Francisco. They marched down the main street of the city – while wearing silk robes – when California held a parade to mark the state's admission to the Union in 1850. One account says Governor John McDougal believed laborers from China might be used to drain the state's swamplands.

Were the Chinese simply lured by gold and silver? This is a salient question. The Conquistadors of the Spanish Empire were also enticed by precious metals – at least in part – although they sailed across the Atlantic instead of the Pacific. In fact, when the Spanish sailors and explorers first viewed the Pacific Ocean, it looked serene to them. So they called it "Pacific," meaning "calm" in the Spanish language. Vasco Nunez de Balboa was the first European to see the Pacific. He did so from a mountaintop in Panama in 1513. Balboa first sailed to South America in 1501. He later became a pig farmer, which paved the way for the very strange notion that men brave and daring enough cross giant oceans will eventually have to engage in humble, menial pursuits.

As for the Chinese laborers, they made a daring voyage across the Pacific Ocean while indentured to very rich and well-connected merchants. This was no ordinary journey. The Pacific is almost 60 million square miles and is by far the world's largest ocean.

The Opium Wars of 1839-1842 and 1856-1880 saw the British Empire sell (at gunpoint) opium to everyday ordinary Chinese. This was done despite the warnings of the ruling Qing political elite not to do so. The Opium Wars led to China incurring great debts to the West. Taxes on ordinary Chinese were raised to pay these debts. By 1849, many men in China were ready to seek better fortunes in California. And they achieved much despite great odds.

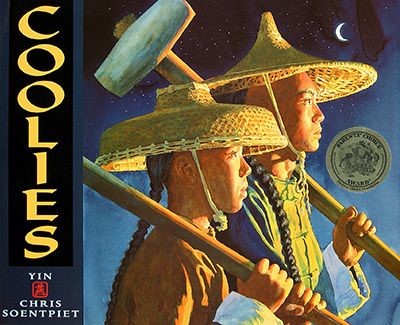

As is so often the case with many manual laborers, the Chinese were looked down upon. This slander occurred despite their hard work, endurance, strength, self-sacrifice and commitment to a greater good beyond themselves. They were called "coolies." Where does this offensive word originate? Some say it comes from the Tamil (Sri Lankan) word "kuli" meaning "wages." (Certainly there is nothing slanderous or wicked about that word.) Then there's the Chinese character 苦力 or "pinyin." This refers to a "bitterly hard (use of) strength" or "bitter labor."

After slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1807, the need for hard laborers increased. Asians – mostly from China and India – filled this void, working in British Empire colonial outposts and backwaters ranging from the Caribbean to South Africa to Latin America. They worked in the Guano Pits of Peru. They worked in Trinidad. They worked in Cuba. Some had been sold into servitude through clan violence. Some were forced into this mad game because they needed to pay off the gambling debts they had incurred. The government of China and the British Empire both sought to protect the rights of these workers, yet there can be no doubt they were exploited. Of course this cannot take away from their larger-than-life achievements.

As the 1849er Gold Rush began to wane, a "timber rush" for redwood and Sequoia emerged. Resentment against the Chinese laborers grew. In the 1870's, Chinese immigration to California was actually double that of Anglo immigration. This led to resentment and state and national legislation to curb Chinese immigration. (California passed state legislation in 1870 outlawing "coolie" servitude as being akin to human slavery.) They were hounded by angry vigilantes. Often they performed a great deal of dangerous and even menial work, including laundry.

Considering the success of LeEco and similar Chinese companies in California today, these humble, brutal beginnings for the Chinese seem almost unimaginable. Yet bitter struggle often makes men physically and morally stronger. (Images and exhibitions about the Chinese immigrant experience can be found here and here.)

That said, working on the transcontinental railroad seemed a logical outlet for these hard working Chinese immigrants. It should be noted that the hardest part of building the transcontinental railroad involved the segment through the Sierra Nevada. This is where the Chinese performed their greatest labors – with the help of nitroglycerin. It was cold and dangerous. There was snow and ice. They did not speak English well or at all. But they adapted.

One of the ways they adapted was through "I Ching."

According to the New York Review of Books, I Ching:

"… {H]as served for thousands of years as a philosophical taxonomy of the universe, a guide to an ethical life, a manual for rulers, and an oracle of one's personal future and the future of the state. It was an organizing principle or authoritative proof for literary and arts criticism, cartography, medicine, and many of the sciences, and it generated endless Confucian, Taoist, Buddhist, and, later, even Christian commentaries, and competing schools of thought within those traditions. In China and in East Asia, it has been by far the most consulted of all books, in the belief that it can explain everything."

Following along with the philosophy of I Ching, this series on the role of Chinese immigrant labor in the building of the transcontinental railroad will attempt to explain everything and everything imaginable about this massive, incredible feat that still echoes through the annuls of history. The History Channel addressed this giant railroad on their show "Modern Marvels."

There was a great deal of ugliness involved to be sure. And as is so often the case in our imperfect world, the good and the bad, the positive and the negative, somehow had to coexist side by side at every turn.

-

What will a Trump Presidency mean for self-driving cars?

-

Driverless Cars – an anti-social future in the making?

-

Ambulance + Tank =’s a new generation of emergency vehicle technology

-

The Israeli Army’s new autonomous vehicle – a look at the battlefield of tomorrow

-

Top 10 Newfangled Car Safety Technologies

-

The Fall Leaves of Yosemite – Celebrating 100 Years of U.S. National Parks

-

Stephen Hawking, Robotics and Our “Dangerous Point in Human History”

-

Do auto manufacturers or tech companies file the most patents?

- “Data is the New Oil” - The Alpha, Beta and Omega of Postmodern Wealth Creation - Part I

- A Brief History of the Internet

- Is mankind living in a computer simulation? Part Ⅰ

- The Wind Beneath My Wings "Altamont Wind Farm"

- Information Overload – How Much is too Much?

- “Data is the New Oil” - The Alpha, Beta and Omega of Postmodern Wealth Creation - Part II

- XPeng Motors Valued at Over $8.4 Billion Files for U.S. IPO, the Company is Backed by Alibaba and Xiaomi

- The Lost Legion of Crassus

- California, Chinese Pride and the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad Part I

- California, Chinese Pride and the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad Part II

About Us

About Us Contact Us

Contact Us Careers

Careers